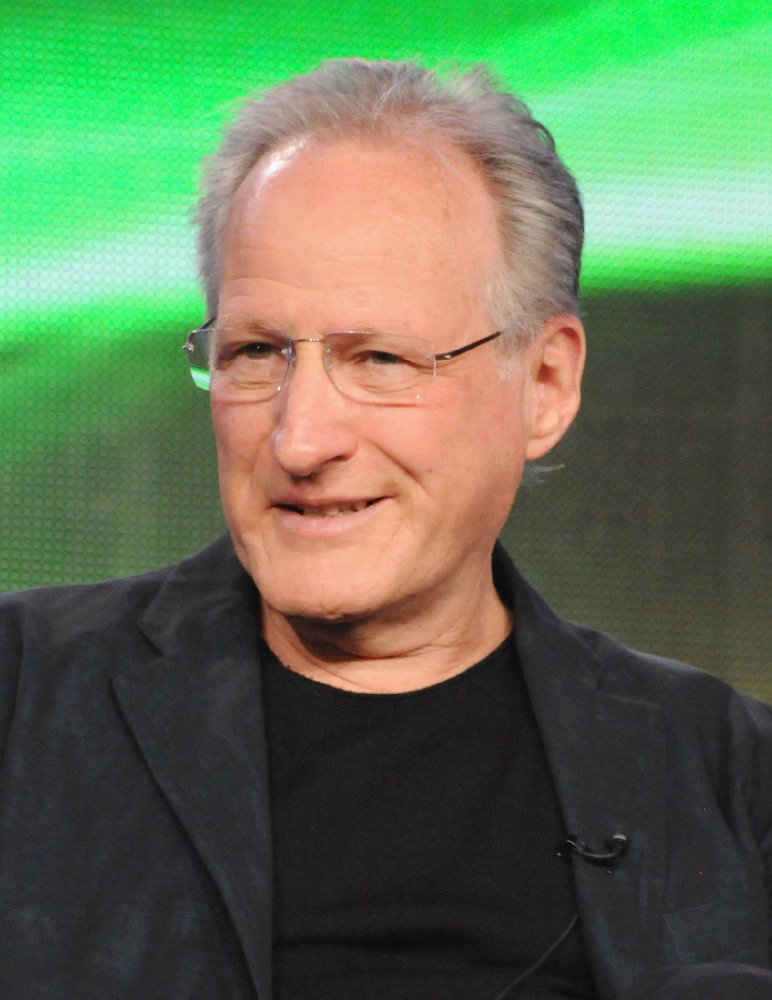

Michael Mann

Birthday: 5 February 1943, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Birth Name: Michael Kenneth Mann

Height: 173 cm

A student of London's International Film School, Michael Mann began his career in the late 70s, writing for TV shows like Starsky and Hutch (1975). He directed his first film, the award-winning p ...Show More

[on working with Daniel Day-Lewis on The Last of the Mohicans (1992)] 'Hawkeye' is pretty close to w Show more

[on working with Daniel Day-Lewis on The Last of the Mohicans (1992)] 'Hawkeye' is pretty close to who Daniel is as a person. Daniel is a deep, romantic man with a very strong value system. He's kind of classic. He's drawn to see great values in simple things. He's somebody who eschews celebrity. He and Rebecca [wife Rebecca Miller] have a very strong family, a real literary sensibility. Hide

[on how important the use of widescreen (1:2.35) is to him] Very. It's important to me for two reaso Show more

[on how important the use of widescreen (1:2.35) is to him] Very. It's important to me for two reasons. One, because this [The Keep (1983)] is an expressionistic movie that intends to sweep its audience away - be very big, to have them transport themselves into this dream-reality so that they're in those landscapes, there with the characters. You can't sweep people away in 1:1.85 and mono. Also, I'm just not interested in 'passive' filmmaking, in a film that's precious and small and where it's up to the audience to bring themselves to the movie. I want to bombard an audience - a very active, aggressive type of seduction. I want to manipulate an audience's feelings for the same reasons that composers write symphonies.[Dec. 1983 in Film Comment] Hide

[on his ambition as a director] My ambition was always to make dramatic films. I had a strong sense Show more

[on his ambition as a director] My ambition was always to make dramatic films. I had a strong sense of the value of drama growing up in Chicago, which has long had a thriving theater scene. I'd also found, working a lot of odd jobs as a kid-as a short-order cook, on construction, or as a cab driver-that there was tremendous richness in real-life experience, and contact with people and circumstances that were sometimes extreme. I was drawn to this instinctively. You find out things when you're with a real-life thief, things you could never make up just sitting in a room. The converse is also true: Just because you discover something interesting, you don't have to use it; there's no obligation. Yet life itself is the proper resource.[2012] Hide

[on The Keep (1983)] There occurs a moment in time, when the unconscious fears of society become ext Show more

[on The Keep (1983)] There occurs a moment in time, when the unconscious fears of society become externalized reality. In the 20th Century this time was manifest in the Fall of 1941. What Hitler promised in the beer-gardens had actually come true. The Greater German Reich was at its apogee: it controlled all Europe. The war was won. And the dark psychotic appeal underlying the slogans and rationalizations was making itself manifest: the camps were being made ready. That was the setting F. Paul Wilson selected for his story and it works very well in the context of of a fairy tale for grown-ups. But the last thing I wanted to do was another street picture. I wanted to do something very stylized both in cinematic and in narrative form. And fairy tales evoke very strong emotions because they communicate on an internal level, to our unconscious desires and images, as opposed to a fable or a myth which approaches us on the level of conscious behavior. And fairy tales have the power of dreams - only from the outside. So I decided to stylize the art direction and photography, but use realistic characterization and dialogue. [Fantastic Films, March 1984] Hide

[on Thief (1981)'s soundtrack] Earlier, I had been divided between choosing music regionally native Show more

[on Thief (1981)'s soundtrack] Earlier, I had been divided between choosing music regionally native to Thief (1981), Chicago Blues, or going with a completely electronic score. The choice was intimidating because two very different motion picture experiences would result. Right then, the work of Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk and 'Faust' was an explosion of experimental and rich material from a young generation coming of age out of the ruins and separating itself from WWII Germany. It was the cutting edge of electronic music. And, it had content. It wasn't sonic atmospheres. There was nothing in the UK or the States like it. Further, there was a relationship between the blues and Edgar Froese because he had started out as a blues guitarist. Even though their music was electronic, it had a twelve bar blues structure to most of it. More importantly he, as an artist and a man, was connected to the material reality of life on the street and he found musical inspiration there, as does the Blues. Culturally, he was attuned to the politics of the '60s and '70s. (...) Berlin was still steeped in its recent history and its history... the Wall, shrapnel damage to building facades...was still evident. The score was adventurous with some real voyages of discovery. Working with analog sequencers and synthesizers we were also processing sound effects, which I had brought in a suitcase on mag, so that ocean waves might crash in G Major, the same key as the cue. It was a wonderful artistic collaboration. Thinking back to what was at the time cutting edge technology but so primitive now, it was more fun. They were innovating processes and re-combining components to do stuff on frontiers that Moog never envisioned, as new ideas showed up. It was Edgar's open spirit and embrace of possibilities that made it all occur. A somewhat unique soundtrack for its time was the result. Working together with band-mates Johannes Schmölling and Christopher Franke with Froese in the lead in a gutted movie theater, hard by the Berlin Wall, it seems like not so long ago and it was the best of times.[2015] Hide

[on Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)] It said to my whole Show more

[on Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)] It said to my whole generation of filmmakers that you could make an individual statement of high integrity and have that film be successfully seen by a mass audience all at the same time. In other words, you didn't have to be making Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954) if you wanted to be a part of the commercial film industry, or be reduced to niche filmmaking if you wanted to be serious about cinema. So that's what Stanley Kubrick meant, aside from the fact that I loved Kubrick and he was a big influence.[2006] Hide

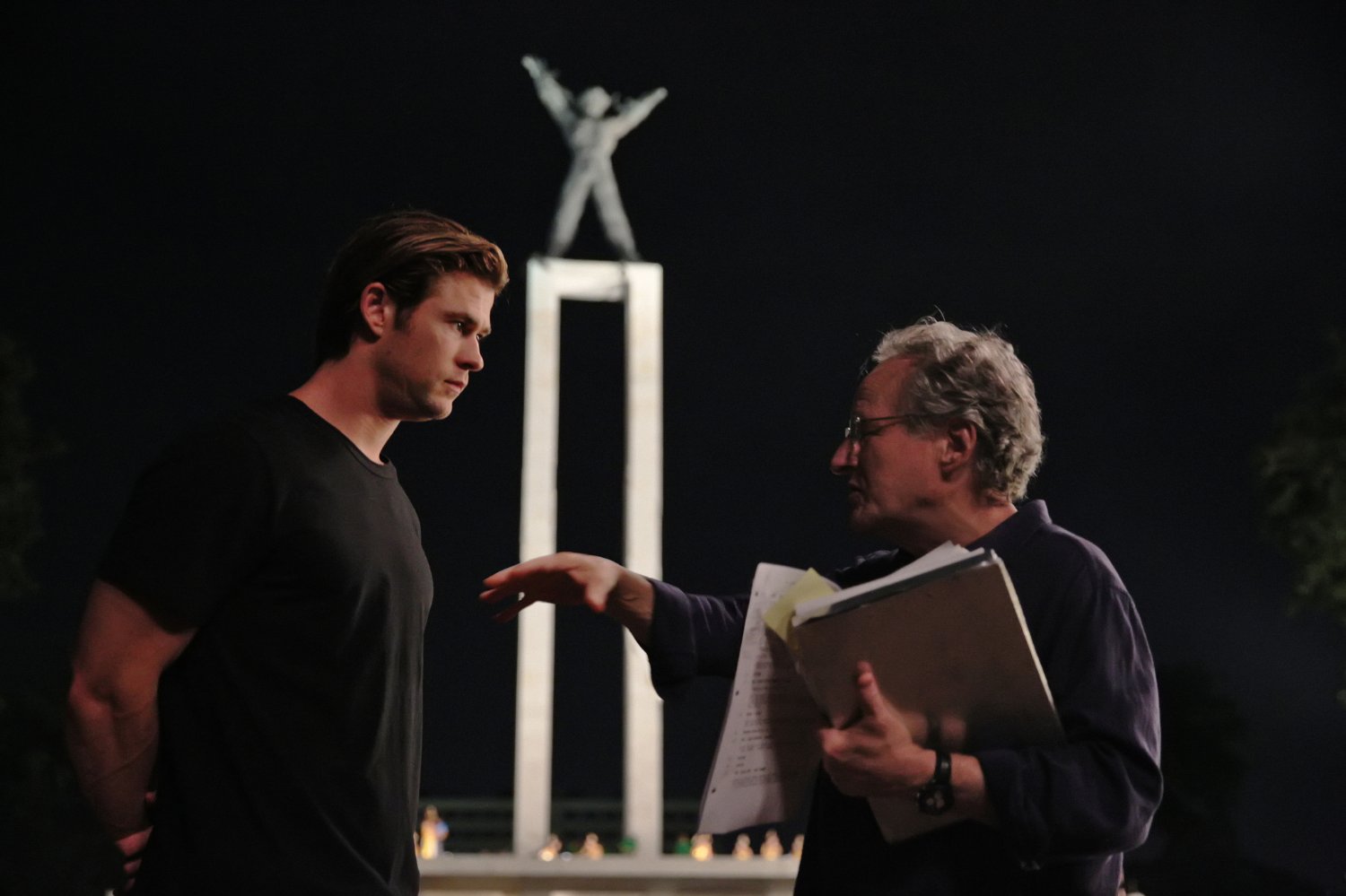

[on Collateral (2004)'s use of High-Definition Digital Video] So my reason for choosing DV wasn't ec Show more

[on Collateral (2004)'s use of High-Definition Digital Video] So my reason for choosing DV wasn't economy but was to do with the fact that the entire movie takes place in one city, on one night, and you can't see the city at night on motion-picture film the way you can on digital video. And I like the truth-telling feeling I receive when there's very little light on the actors' faces - I think this is the first serious major motion picture done in digital video that is photoreal, rather than using it for effects. DV is also a more painterly medium: you can see what you've done as you shoot because you have the end product sitting in front of you on a Sony high-def monitor, so I could change the contrast to affect the mood, add colour, do all kinds of things you can't do with film. Digital isn't a medium for directors who aren't interested in visualisation, who rely on a set of conventions or aesthetic pre-sets, if you like. But it's perfect for someone like David Fincher or Ridley Scott - directors who previsualise and know just what they want to achieve.[2012] Hide

[on producing films] One of the most instructive events was when, right out of the London Film Schoo Show more

[on producing films] One of the most instructive events was when, right out of the London Film School, I got a job working for Bill Kaplan in the British office of 20th Century Fox in Soho Square. Bill was production supervisor for a lot of films that were being made at that time in England, owing to the budgetary rebates then in force under The Eady Plan. Working in physical production, helping organize scheduling, budgeting, and production logistics became for me a model of how to think, of how to organize the totality of a movie. I apply the lessons I learned there to this day, not just in terms of budgeting-but in terms of the content of a movie. There's a critical planning that is very three dimensional at this early stage. That has become really important in everything I've done since.[2012] Hide

[on critics] If somebody asked me, "What's "Thief" to you?": To me, it's a left-extensionalist criti Show more

[on critics] If somebody asked me, "What's "Thief" to you?": To me, it's a left-extensionalist critique of corporate capitalism. That's what Thief (1981) is. What is interesting is that no critics in the U.S. got that, no critics in the U.K. got it. Every critic in France got it when the film came it. It was like this crazy kind of cultural litmus test or something.[2015] Hide

[if there is one film he wished he could make again] Probably The Keep (1983).[Laughs.] (...) It was Show more

[if there is one film he wished he could make again] Probably The Keep (1983).[Laughs.] (...) It was a script that wasn't quite ready, and, [a hard] script to schedule, because of how the picture was financed. And a key guy in the making of it, a man named Wally Veevers, who was a brill - wonderful, wonderful man, who was a very talented visual effects designer from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) all the way back to Things to Come (1936), tragically passed away, right there in the middle of our post-production. And, so it became for me, a film that was never completely, never completely realized.[2014] Hide

[on the theatrical experience] In the Thirties and Forties people saw a movie once or twice a week. Show more

[on the theatrical experience] In the Thirties and Forties people saw a movie once or twice a week. Now people see moving pictures six hours a day. So what's the motivation to go to the cinema? It has to be to have a different order of experience. Otherwise stay home and watch the idiot box [TV]. Cinema has to be more experimental, it has to transport people away, it has to provide them with a suspension of disbelief, a feeling they've been swept up into another reality they can't get when they're bigger than the image.[1983 in Film Comment] Hide

[on his racetrack series Luck (2011)] It's about the basic yearning, that impulse, to somehow ventur Show more

[on his racetrack series Luck (2011)] It's about the basic yearning, that impulse, to somehow venture skills, hope they'll collide with the opportunity and yield a change in your material circumstances. That hope for an outcome, that transcendence, is what the show is really about. Hide

[on why he became a director] I wasn't really interested in cinema until I saw Dr. Strangelove or: H Show more

[on why he became a director] I wasn't really interested in cinema until I saw Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), alongside a set of films by F.W. Murnau and Georg Wilhelm Pabst for a college course. These were a revelation. I'd already seen some of the French New Wave and some Russian films, but the idea of directing, of shooting a film myself? Never. Prior to "Strangelove", it simply had not seemed possible that you could work in the mainstream film industry and make very ambitious films for a big mainstream audience. The whole film is a third act. The mad general played by Sterling Hayden is totally submerged in his character the moment we first encounter him. There's no prelude, no context. We're just with him, we know who the guy is, and we catch up along the way. Even as a young man I found that intensity very exciting-how immediate it was.[2012] Hide

[on art] I don't make much of a distinction between genius design and engineering and athletic perfo Show more

[on art] I don't make much of a distinction between genius design and engineering and athletic performance and great works of art - it's all the human nervous system seen from the inside out. What allowed Muhammad Ali to do the so-called Ali Shuffle is no different from what inspired Antonio Vivaldi.[2015] Hide

[on the cinematic experience] A 65-ft.-wide screen and 500 people reacting to the movie, there is no Show more

[on the cinematic experience] A 65-ft.-wide screen and 500 people reacting to the movie, there is nothing like that experience. Hide

[on his artistic ambitions with The Keep (1983)] I'd just done a street movie, Thief (1981). A very Show more

[on his artistic ambitions with The Keep (1983)] I'd just done a street movie, Thief (1981). A very stylized street movie but nevertheless stylized realism. You can make it wet, you can make it dry, but you're still on 'street'. And I had a need, a big desire, to do something almost similar to 'Gabriel Garcia Marquez''s "One Hundred Years of Solitude"[1967], where I could deal with something that was non-realistic and create the reality.[Dec. 1983 in Film Comment] Hide

First of all The Keep (1983) is not a 'war movie'. It takes place during 1941, but that may be a mis Show more

First of all The Keep (1983) is not a 'war movie'. It takes place during 1941, but that may be a misimpression. What "The Keep"(1983) really is, is an adult fairy tale, a fable, a romance and a horror story. It's very intense. I've got to go back to Jean Cocteau's La belle et la bête (1946) which is a very simple story. The strength of that movie is the fact that it is a fable. As you analyze and think more about it, more starts coming out of it. Why did I get into 1941 and why did I pick that period? All fables deal with good and evil and so does this one. But obviously, this movie is not the first one ever to be set during the Second World War. And it's also not the first movie with elements of the supernatural. So for me, it had to be like no other movie ever set during W.W. II. It had to be original and unique, and it had to be like no other movie with supernatural entities. So what I had to do was to write the screenplay myself. It's taken from the book by F. Paul Wilson, but it's largely an adaptation in the sense that I departed from the book substantially.[Fantastic Films, March 1984] Hide

[on his crew] If people are as ambitious as you are, you keep them close to you. If a person gets ex Show more

[on his crew] If people are as ambitious as you are, you keep them close to you. If a person gets excited by the things I am excited by - say, transforming a run-down arena in the middle of Mozambique that hasn't had electricity or plumbing since 1974, as we had to do for Ali (2001) - if a challenge like that gets your blood running, you would be a person I gravitate toward. We would wind up working together on a lot of pictures.[2012] Hide

[on directing] I always try to find something that makes a scene feel real, and what makes things fe Show more

[on directing] I always try to find something that makes a scene feel real, and what makes things feel true to me is usually something anomalous, a component you would never expect to find, so it doesn't look manicured or perfect. This can be a location, a gesture, an expression, a thought in somebody's head - if you look at life, that's what it's like.[2012] Hide

[on shooting Collateral (2004) mostly in HD] With film, you don't have any depth of field. I wanted Show more

[on shooting Collateral (2004) mostly in HD] With film, you don't have any depth of field. I wanted to see way into the distance, two miles down the street. I wanted to see like the burnt umber that's like a ceiling in this city, that reddish glow on the marine layer 900-1200 feet up, and see deep into the city and the sodium vapor and everything that makes that color. That had to be digital. But there weren't even look-up tables, the equivalent of a color table. We invented all of that, myself and [Second Unit Director & Associate Producer] Bryan H. Carroll, actually.[2015] Hide

[on music] As research, music enters early for me. If you can find that piece of music which evokes Show more

[on music] As research, music enters early for me. If you can find that piece of music which evokes the central emotion of one of your characters, some pivotal crisis where he or she must rouse themselves from despair and manifest something very aggressive within his or her own mind-this becomes the piece of music for that moment. If I want to quantify how a character is feeling and thinking, in a way that is replicable, so I can re-evoke that emotion many, many times, finding the right piece of music is positively essential. Not only as I prepare the scene-but as I shoot the scene, as I direct the actors, and finally, as I edit the scene.[2012] Hide

[on discovering digital cameras] When I first shot some stuff digitally it was in Ali (2001). We wen Show more

[on discovering digital cameras] When I first shot some stuff digitally it was in Ali (2001). We went on the roof of a building in Chicago, we had a couple of cameras and I took a flashlight, bounced it off a card and that was all the lighting. It was very little lighting. And it felt that what I saw was there was a truthfulness to the graphic that just blew me away. It felt like, 'Holy shit. The film crew's not here but this has really happened.' And I tried to define for myself what I was seeing. What I was seeing was the absence of film lighting. We're used to a certain convention of film lighting. It's an artifact, but we're used to it. We applaud when 'Vittorio Storaro'_ does it. It's great. I love it. But when you subtract it, stuff feels real in a certain way. It's all mid-tones. There's no key light and fill. (...) When you eliminate the artifact of theatrical lighting, suddenly truth seems to show up. I believe more that it's really happening. Muhammad Ali is really on that roof. He's really working out. He's distracted by something in the distance and he realizes buildings are burning all over the city, because it's the night Martin Luther King got killed. I just felt that immediacy of it.[2015] Hide

[on the benefits of digital projection] Collateral (2004) was beautiful in digital projection if you Show more

[on the benefits of digital projection] Collateral (2004) was beautiful in digital projection if you were in a theater that had digital projection. The problem was that it had photochemical release prints, which the labs knocked out with 'tolerances' that were a joke. A print any director would reject was fine as far as the lab was concerned. So, getting what I made digitally, to photochemical release printing was a nightmare. Now, with digital cinema being ubiquitous, it's great.[2014] Hide

I don't think you can be good or even aspire to be good, unless you're prepared to push everything a Show more

I don't think you can be good or even aspire to be good, unless you're prepared to push everything aside in your life and just drive to execute your vision of that movie, in such a way that it really communicates to an audience. It's a very difficult thing to do. Hide

The best-kept secret about Don Johnson is the fact that he is a terrific actor.

The best-kept secret about Don Johnson is the fact that he is a terrific actor.

Could I have worked under a system where there were Draconian controls on my creativity, meaning bud Show more

Could I have worked under a system where there were Draconian controls on my creativity, meaning budget, time, script choices, etc.? Definitely not. I would have fared poorly under the old studio system that guys like Howard Hawks did so well in. I cannot just make a film and walk away from it. I need that creative intimacy and, quite frankly, the control to execute my visions, on all my projects. Hide

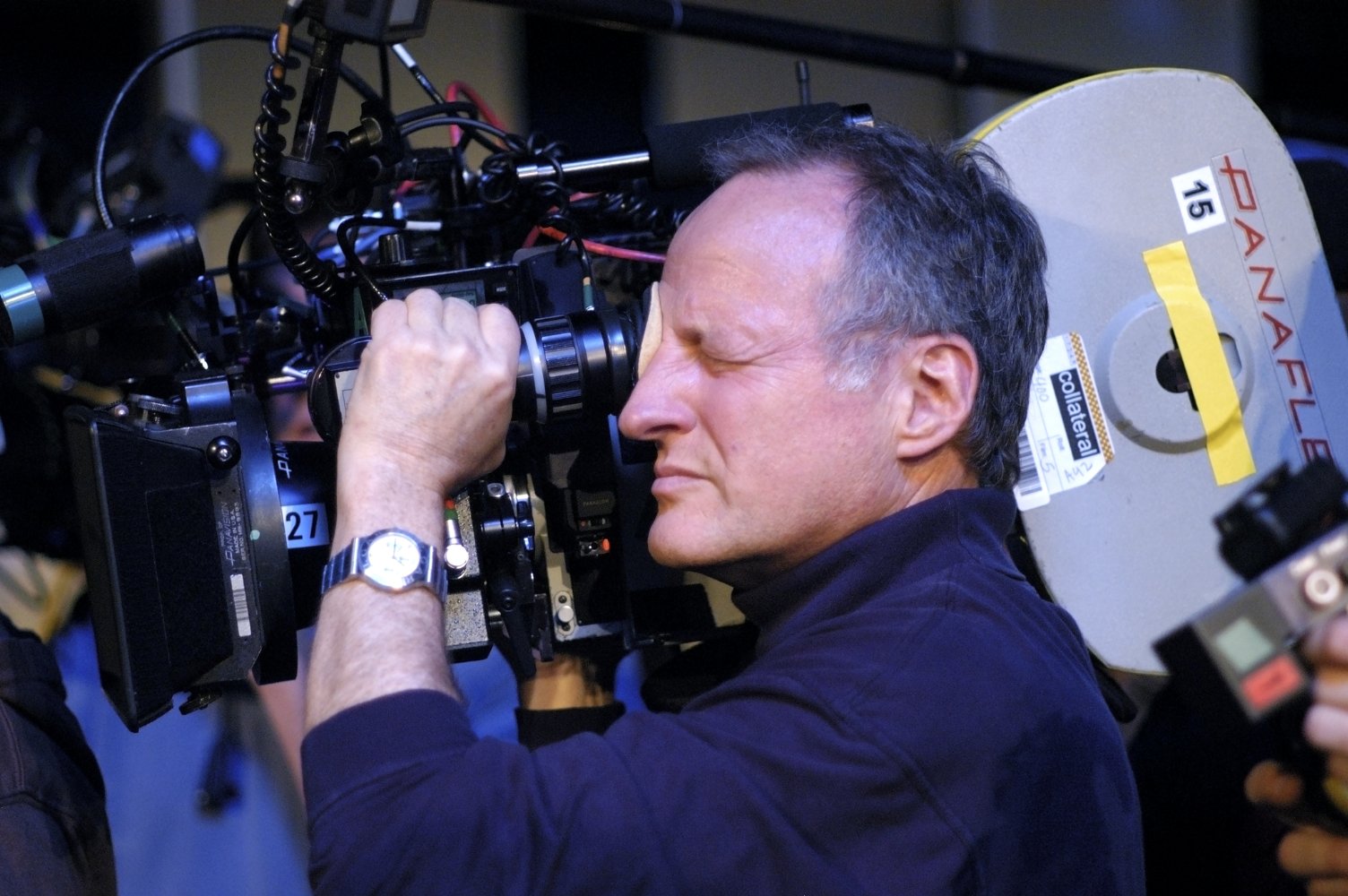

[on whether he operates the camera] The criterion is when I want to see what's going on through the Show more

[on whether he operates the camera] The criterion is when I want to see what's going on through the lens. Usually, it comes down to performance more than technique . . . I've also worked with the same camera crews, even down to the assistants, on the last four films. So, we've developed a family in camera. A family that picks right up where they left off every few years. I see the world from the perspective of a 5'8" person, not someone who is 6'4". so naturally, I'm going to choose certain lens heights over and again . . . Sometimes nature makes choices for you.[1999] Hide

[on how he picks composers] Composing is kind of like casting. On a given picture with a standout co Show more

[on how he picks composers] Composing is kind of like casting. On a given picture with a standout composer, like Elliot Goldenthal, who I think is one of the more extraordinary composers working today, I will use only his score because I want the picture to have a unified sensibility, like in Heat (1995) or Public Enemies (2009). It was the same with Trevor Jones on the main themes of The Last of the Mohicans (1992). Randy Edelman did some additional work that was excellent. In other films, I'll use more than one composer because I want to rotate among different emotional perspectives. That could be character-driven or something totally different about the circumstances, such as the ending of Ali (2001) when we're in Africa for the 'Rumble in the Jungle' and the music is almost wall-to-wall Salif Keita. One composer may be able to evoke certain emotions, and another composer is better for different passages. I did that in Collateral (2004) as well as in Blackhat (2015).[2015] Hide

I think it's easy for directors to stay fresh more than actors, especially once an actor becomes a s Show more

I think it's easy for directors to stay fresh more than actors, especially once an actor becomes a star. It's hard for Russell Crowe to walk down a street or take a subway. I can fly coach. Hide

[on influences] You're influenced by who you like. I like Stanley Kubrick, I like Alain Resnais imme Show more

[on influences] You're influenced by who you like. I like Stanley Kubrick, I like Alain Resnais immensely. I like Andrei Tarkovsky, although there's very little in Tarkovsky I'd want to do myself. In fact I fell asleep through half of Solaris (1972), but I still love it. And Stalker (1979). He has a Russian, suffering nerve of pace that it's hard to relate to, but you can't help being impressed and moved by what you see.[Dec. 1983 in Film Comment] Hide

Michael Mann's FILMOGRAPHY

All

as Actor (13)

as Director (10)

as Creator (6)